There have been many changes in the way wines are sold in restaurants since the late 1970s, when I started in the business. At the same time, a lot has not changed at all.

What’s gone unchanged is the most basic principle: A profit must be made. To accomplish this, it’s always been pretty much the accepted rule that the sum total of variable (or prime) costs—such as labor, liquor, beer, and of course, wine and food—must never exceed 65%. Most restaurants, after all, need at least 30% to cover fixed costs, such as occupancy and utilities, in order to have enough left over for cash flow, profit, and possible raises for you.

Sommeliers: Why else do you think your owners—or upper managers, whose salaries or bonuses are typically tied directly to cost control—never stop hammering you about keeping your wine costs down to, say, 33% (the classic three-times markup)? Simply put, if you can’t keep your wine cost in line, other costs need to go down in order to make up for the loss and sustain a restaurant. Screwing up on costs is tantamount to getting yourself fired, if all you're doing is helping your employer go out of business.

One way or another, wine cost affects everything a restaurant does. If your wine cost starts to rise to 40%, then food costs, which are typically around 30%, would need to get closer to 25%. To do that, your chefs either have to start using cheaper ingredients (it’s hard to be “farm-to-table” when you’re buying exclusively off a Sysco truck), or entrée prices need to rise from $15-$30 to $40-$60. In most markets, doing the latter effectively narrows your customer base.

The other option is for liquor costs (for most restaurants, kept around 20%) and beer (usually around 30%) to start to overperform. You could also cut labor, which, of course, could severely compromise service—and nothing is more important in a restaurant than service. Something has to give if your wine prices get out of line, especially when sales falter—and virtually every restaurant has its down times, whether seasonal, due to the inevitable ebbs and flows of the economy, or nowadays, natural disasters or national health crises.

At the same time, as sommeliers we need to sell wine. No one is arguing with the fact that it is a lot easier to sell a fantastic bottle of Pinot Noir for $50 to $75 than for $100 to $150. As a wine lover at heart, your instinct to keep prices down is entirely correct. Better wines tend to cost more, and the better the wine you can sell, the better the dining experience will be for your guests.

Plus, consumers aren’t stupid: They’re not oblivious to restaurants with better wine prices than others. They can be resentful of having to pay a lot more for wine in a restaurant than they would in a retail store. Then again, restaurant owners tend to get extremely resentful when you don’t hit your bottom line.

So what are the options? In the 1970s, at New York’s legendary Windows on the World, Kevin Zraly began to implement a markup system designed to stimulate sales of higher quality wines by pricing them on a steep curve: Lower cost wines were marked up the highest to generate the most revenue, and higher priced wines were marked up the least to stimulate interest.

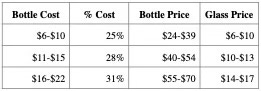

The exact system proffered by Zraly during the ‘70s:

No one, at that time, sold as much wine as Zraly. Windows on the World may have been an extravagant restaurant, but guests could get an extravagant wine experience for a fair price at Windows. But since those glory days, the bottle (i.e., wholesale) costs of wines have obviously increased dramatically—the lowest cost wines sold in today’s fine dining restaurants start at $10-$20—and sales of ultra-premium wines by the glass are a much bigger factor in our programs.

Forty or fifty years ago, glass programs usually consisted of generic Burgundy, Chablis and Rosé, and given that unsavory option, wine drinking guests were deliberately “pushed” into buying higher quality bottles. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that “fighting varietals” (in those days: Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon and White Zinfandel) became prevalent in the industry. Alternative wines by the glass—such as Pinot Noir and Pinot Gris, or high-quality imports, from Albariño to Zweigelt—didn’t pop up on our radars until the mid-1990s. These weren’t good ol’ days—these were downright dreary days.

Given the welcome changes in the taste of today's consumers, the following is a basic model demonstrating how Zraly’s sliding scale might probably work in the 2000s.

Wines By the Glass:

Bottle List:

In the contemporary model, the blended cost of glass-plus-bottle sales typically hovers between 31% and 35%. A big negative is the reliance upon higher markups in the glass program: If this is something you are not high on—there is a lot to be said for reasonable glass prices, especially if glasses are as much as 80% of your sales—the only alternative is to keep glass prices down. But that requires increasing markups on bottles in order to end up at a 31%-35% blended wine cost. If you are reluctant to raise bottle prices, overall blended wine costs could creep up to 40%. But if your boss is unsympathetic to 36%-40% costs, the remedy is to do the math, and make the proper adjustments to establish a curve that works for your restaurant—your balance of glass vs. bottle sales.

Wine sales, of course, are never driven by price alone. It always involves savvy selection, intelligent merchandising and relentless training. If you do the work, you make the sales and hit your cost objectives. Zraly, for his part, has often been quoted as saying that out of the thousands of wines that he would list at any given time, 80% of the sales consistently came from only about 40 selections—the rest, as he put it, was “window dressing.” This probably holds true today, even in the most successful restaurants.

Knowing the math, it makes sense to maintain the strongest focus on your 40 or so core wines: If these are the wines that sell the most, make sure these are the wines that are most simpatico to your cuisine, most representative of your identity and, above all, most likely to meet your company's profit goals.

Thanks for sharing. This sliding scale is used in most restaurants in Spain and it ensures that the restaurant is meeting its profit goals on each bottle while making higher and bottles more attractive. Even with lower margins at the high end of your list, selling more expensive bottles is more profitable in absolute terms.