Consequences of misperception (or, why wine myths die hard)

From the chapter: Service service service

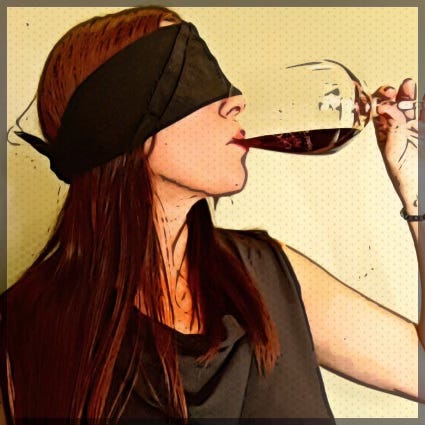

The wine world has always been full of myths. Why? Because mystique and imagination play as big a role in the enjoyment of wines as facts and figures. Wine, after all, is often described as an art, and leaps of imagination are very much a part of all artistic mediums.

As you would expect, almost all myths are eventually dispelled, at which point they are replaced by inconvenient truths—things that most people can't or won't accept, even when we know they're true. We like our mystiques, which is why we keep them around long after they stop making sense or add up to anything beneficial.

For example, when I first started in the industry during the late 1970s it was "common knowledge" that the finest wines in the world came from France, and that wines from the places such as California or Oregon were, at best, pale imitations. As we all know, events such as the Judgement of Paris in 1976 quickly put an end to that errant assumption.

The more I've thought about the Judgement of Paris, though, the more I've come to the conclusion that what it really demonstrated is the fact that taste in wine is, and always will be, highly subjective, and based primarily on experience—or lack thereof, in the case of those judges in Paris, back in 1976.

That is to say, you can bet that the French judges in 1976 truly believed, when handing in their scores, that they were rating French wines higher than California wines. The problem was that they had zero experience tasting California wines, and simply rated the wines the way most wine professionals rate wines, which is by awarding the most points to the wines with the greatest intensity—and California wines then, as they still are today, are plenty intense.

We now know, of course, that the best wines of the world are about a lot more than intensity. There are other important factors to consider when weighing quality—such as balance, harmony, sense of place, pedigree, and the myriad terroir-related distinctions that make each well made wine different from others. No matter, because after 1976 the entire world learned that California wines can be just as good as any other wine in the world, especially in terms of that aforementioned quality, intensity. It was a good thing, even if misleading.

And the American wine industry has taken it to the bank. We are proud inventors, for one, of the 100-point system of rating wines; which, if anything, has only reinforced the idea that intensity matters most, and has become a tool of the industry's myth-making. Because no matter how you slice it, numerical scoring is no more than a way of measuring intensity, largely in lieu of other sensory factors. The pretense is typically backed up by the claim that wines are tasted blind (although many critics don't bother to pretend), and therefore "objectively." The intrinsic problem is that, in the absence of knowing a wine's origin or brand, virtually all critics who taste wines blind take the obvious fallback position: The more intense the wine, the higher the score. Terroir-related distinctions be damned.

We may truly want to believe that a 95-point wine is better than a 89-point wine, but logic also tells you that the critics or magazines conjuring up these scores are as partial (i..e., subjective) as anyone, whether wines are tasted blind or not. All quality ratings are personal, or the opposite of objective. Putting numbers on wines is like putting numbers on anything else that is personal. What if, for instance, we did the same thing with music? It would be like giving The Beatles' "Yesterday" 95 points and The Rolling Stones' "Paint It Black" an 89, when in reality you may very much prefer "Paint It Black" and despise "Yesterday." It would be like rating Beethoven's 5th a 100, and Mozart's Requiem a "mere" 95. Of course, this is all absurd, but absurd is exactly the way most wines are being sold today.

For the unsuspecting consumer, the bigger danger of numerical ratings is that the numbers never tell you what wines are best for you. It is like having "Yesterday" rammed down your throat even though you can't stand it. Or being forced to listen to Requiem when you'd much rather hear Ludacris or Taylor Swift. Tastes in wines, like tastes in music or any of the arts, are so wide ranging and varied, it is simply not possible to convey quality or ultimate appeal through numbers, yet numbers are exactly what is applied almost universally throughout the wine industry.

100-point apologists, of course, will always tell you that scores are still the best way to advise consumers, and to celebrate wines. No, it's not. The New York Times, for example, publishes a "Book Review" every Sunday covering dozens of works of fiction and nonfiction chosen by the publication's staff. They are called "critics," but instead of numerical ratings these writers employ what all wine critics should seriously consider when communicating assessments: Words. The Times uses words to summarize each book, parse distinctions and highlight significant elements even while pointing out strengths and weaknesses. The benefit is we get the information necessary to know about the books we might want to buy.

Yes, it is assumed that readers of The New York Times Book Review are smart enough to figure things out without some critic dumbing all that information down through arbitrarily assigned numerical scores. And guess what, readers do just fine! It doesn't take a genius to understand written reviews. So why is it that we treat wine consumers as if they were too stupid to do the same⏤to understand good and reasoned description of a wine?.

The issue is that the application of scores usually ends up precluding information useful to actual consumers. There might be written words, but words become secondary. Worse yet, in actual practice descriptions found in wine reviews easily become perfunctory; more like laundry lists of descriptors barely distinguishing one wine from the other. Reading 100-point reviews is like taking a sleeping pill. Numerical scores, on the other hand, cannot impart the nature of sensory qualities. They can only impart quantitative value... of what, who knows? It is the laziest way of evaluating wine there is.

At the moment, we might not be successful demanding that the wine media decease and desist from this absurd, irresponsible practice, but we sure as hell can ignore it.

You might have heard, in fact, that many of today's working sommeliers completely ignore wine scores when going about their daily work of tasting and evaluating wines for the purpose of selecting their wine lists. Many of them are smart enough to know that choosing wines on the basis of numbers is doing a disservice to their guests. In the world of higher end restaurants, at least, scores hold little credence.

The 100-point score system, you can say, is what the American wine industry hoisted upon itself once it began to hang its hat on the notion that intensity equals quality, but it is not the only mythical concept that has been holding back the industry.

Very recently, one of my brainier colleagues wrote about another myth that has always been repeated as gospel: That, when storing wines, all bottles must be laid on their side to keep corks moist and preventing wines from oxidizing. Yet research going as far back as 2005 has clearly demonstrated that this is simply not true: Not only is there more than enough humidity in bottles to keep corks intact and bottles fresh whether stored upright or laid on their sides, researchers have also found that wines are probably better off when stored standing up! If there is anything that really matters when it comes to long term storage, it is that you still need to keep bottles as close to optimal temperatures (55° to 60° Fahrenheit) as possible, since it is temperature more than anything affects wine quality during cellaring.

Wine geeks, however, are funny people. I seriously doubt any of them have been rushing down to their cellars to stand their bottles up. It's wine geeks, especially, who will also swear until the cows come home by another basic wine maxim, called "breathing"—the opening and/or decanting of young red wines a considerable amount of time before they are consumed. It is the long held belief that the more exposure to air, the higher the quality of wines.

One report that I've always found to be extremely interesting was printed in a 1997 issue of Decanter—the self-proclaimed "World’s Best Wine Magazine”—which once reported on a double-blind tasting involving Hugh Johnson, Steven Spurrier, Serena Sutcliffe MW and Patrick Léon (the latter, at the time, the winemaker for Mouton-Rothschild), who were asked to blind-taste and assess the quality of four wines, a 1961 Mouton-Rothschild, a 1982 Clerc-Milon, a 1980 d’Armailhac, and a 1990 Mouton-Cadet. Each of these wines were:

Uncorked a few minutes ahead of time, and then poured and tasted.

Uncorked a few hours ahead of time, and then poured and tasted.

Uncorked and poured into a decanter a few minutes ahead of time, before poured into glasses and tasted.

Uncorked and poured into a decanter a few hours ahead of time, before poured into glasses and tasted.

Uncorked, and then immediately poured into glasses and tasted (that is, no “breathing” at all).

Guess which wines, across the board, were the ones that this panel of immortals preferred the most? The bottles that were were uncorked, immediately poured and tasted. It turns out that “breathing,” whether for a few minutes or a few hours, didn't “improve” any of the wines at all. If anything, extra aeration proved to be detrimental.

I have, in fact, reported the finding of this impartial panel in a few places over the years, and each time I've gotten pretty much the same reader responses, all of them amounting to this: "That's nice, but in my experience many red wines are definitely improved by decanting and breathing."

What is the explanation for this and other unfounded beliefs that refuse to go away and die? I'd chalk it all up to the stimulus of neural activity in medial orbitofrontal lobes. That is to say, the way the human brain works and organizes thoughts and preferences. The frontal lobes are the cognitive "pleasure center" of our brains, and can be very convincing. This is the part of our heads that rules our perception like a pitiless, ruthless dictator. It harnesses the beliefs that reinforce practices convincing us of what makes wine taste better, and it can send signals indicative of pleasure even outside the actual sensory experience of pleasure⏤that is, pleasurable sensory qualities that do not actually exist and which are, in fact, illusionary.

What in heaven's name am I talking about? One example is the number of studies that have conclusively demonstrated that wines tagged with higher prices consistently result in sensations of more pleasure than that of lower priced wines, and end up being rated "higher" in laboratory settings. In these studies, price tags are typically switched, and the results always remain the same—it is wines carrying the higher prices, not the wines that actually taste better, that increase sense of pleasure perceived by tasters. These studies, mind you, are based upon measurements of physical response, not mental; but because it is the brain that determines perception of pleasure, mental impressions becomes physical,

The established customs of presumably sophisticated connoisseurs of wine, in fact, are perfect examples of the illusionary aspects of wine appreciation. We already know that our brains can convince us of just about anything on an intellectual level, which includes the practices of letting wines "breathe" or laying bottles down in cellars. Make no mistake, these customs exist precisely as a result of how sensory perception works: It is not so much a belief in what makes wines taste better as the fact that wines do taste better to practitioners of these customs. Hence, why these customs die hard.

This is no different from when we are served wines of a certain level of preordained prestige, or which have a specific cachet, like being made by an esteemed winemaker. My experiences as a sommelier are probably no different from that of many others: It is always predictable, for example, to see entire ballrooms of wine lovers swoon with pleasure over wines served from oversized bottles that we know are badly oxidized or seriously tainted by flaws such as Brettanomyces. This is what we often find when we open wines sourced from private collections for large groups. The bottles can't be rejected⏤they must be served "as is." But it doesn't matter one iota: When connoisseurs believe a wine tastes great, it is great. God bless 'em.

Sommeliers have their own challenges to overcome. Today, many of them are often castigated for their penchant for natural style wines, which much of the rest of the industry find to be seriously flawed wines. But are they? My own perspective on natural wines is well documented: Executed with competence, the minimal intervention approach to viticulture and winemaking gives wines the highest percentage chance of expressing terroir, which is the hallmark of all the finest wines of the world. Too many people in the industry would rather capitulate to standardized tastes in wine than consider special attributes in wines, when special attributes are exactly what terroir-focused wines are all about.

Fact of the matter is, if you are a talented enough sommelier you can successfully sell natural style wines whether they are flawed or not because the restaurant setting has a built-in advantage: Almost all wines taste better in a nice restaurant than they would elsewhere. Besides, what is “flawed?” I consider an artificially oaked Cabernet Sauvignon and furniture polish-like Chardonnay or Merlot to be deeply flawed and offensive, yet these are the wines being served in countless restaurants at every moment of the day.

Furthermore, in restaurant settings we have always known that we can exact the same pleasure-enhancing stimulus in guests used by researchers in labs when they switch price tags by the simple act of handling bottles with visible care, especially by pouring them into attractive decanters—a sure-fire way of making guests feel like they are getting more for their money. We shrewdly deceive guests by doing this all the time, just as are we just as cognizant of shrewdly deceiving ourselves whenever we select and serve wines with a certain level of prestige, whether attached to brand names, higher price points or some kind of "natural wine" cachet.

This is always how the prestige wines of the world are sold. We know, simply, that if a wine is perceived as great, it invariably tastes great⏤whether it is great or not.

I think we are all always aware, of course, that there is a good chance that our own perceptions are flawed, or at the very least, easily misconstrued or misinterpreted. All signals to the brain are messages in need of interpretation, and interpretations are never guaranteed correct. Sometimes we have nagging doubts, which is probably healthy⏤like a fail-safe, or override, built into our nervous system. Problem is, it cuts both ways. When our senses, for instance, tell us that a wine is not very good at all, that same override function is just as capable of corrupting that message, and instead convinces us that the wine is actually very good, just the way we like it. "There is nothing to see here," as the mythical master says; intellectually, a sensible acknowledgement of errare humanum est ("to err is human"), as Seneca put it long ago. But at what point does being human get in the way of common sense, resulting in bad decisions?

Being human is probably exactly why many wine myths may never die. It is simply more convenient to keep them around for the sake of people's perceived pleasures, or to preserve a semblance of order in personal or publicly shared belief systems. The wine business is funny that way. For many sommeliers and wine professionals, it is simply much easier to go along with the crowd as if that in itself automatically brings order to the chaos.

It might be true, to some extent, that accepting standardized beliefs is a safer way of doing business, whether it's a majority consensus, or the consensus of a tiny "cool kid" crowd⏤and many of today's sommeliers do indeed find themselves between a rock and a hard place, pressured to conform to either old conventions or to continuously emerging unconventions. I, for one, have never been much of a subscriber of anything. I would rather, as Paul Simon once sang, be like a rock or an island... hiding safe within my room. Mostly because I've always had my own fail-safe—namely, that it is tasting that is believing, rather than believing what we are told.

Long held beliefs? Don't trust them. Things that you might see with your own eyes or taste with your own palate? Go ahead and trust that, but it is good to have doubts and standard procedures for verification, lest you become a victim of your own misperceptions or untoward outside influences.

Running a wine program in the twenty first century is, in a way, like navigating a mental minefield of myths and obsolescences that can be useful, but invariably do more bad than good. When it's time to go, it's time to go.

There is, ultimately, nothing wrong with putting a personal stamp on wine programs; one that you've carved out on your own. Wine lovers, after all, are instinctively drawn to individuality. It just takes courage and, of course, some brains to get it done. Trust, then verify, thyself.

Great article, Randy. Thank you for illuminating the psycho-mechanisms that allow these wine myths to be so pervasive and for sharing your experience on how to (not) deal with those who deny themselves ultimate wine pleasure because they swallowed the wine cult "kool-aid” nonsense rather than learning to trust their own senses.