Adventures on the Wine Route Revisited

Interview with Kermit Lynch, talking about favorite wines past and present

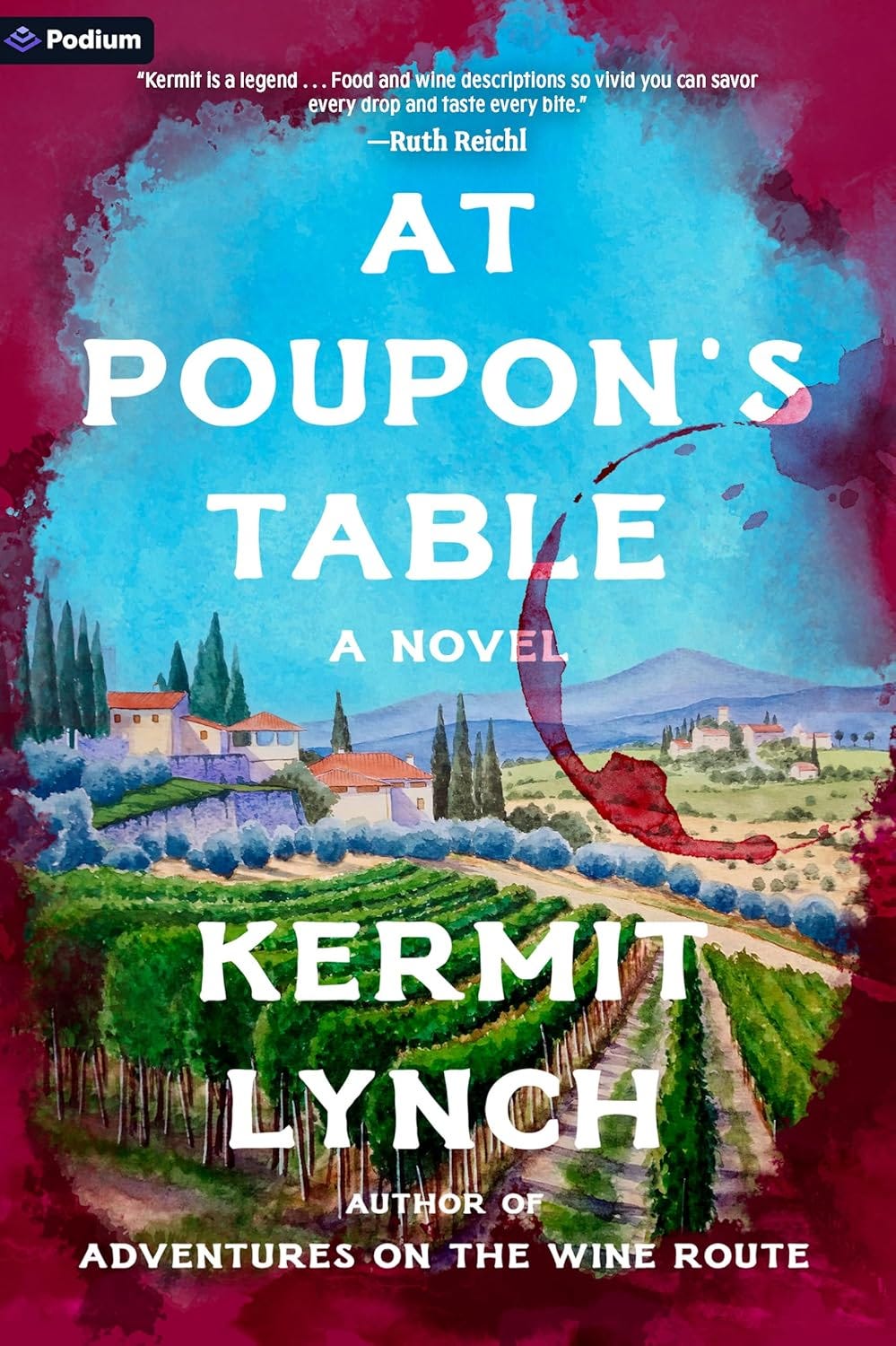

When Kermit Lynch talks, people listen. He has always been the conscience of our industry; even today, a few years into his retirement from his own business Kermit Lynch Wine Merchant. His mind remains restless; having just published his first novel, At Poupon’s Table (2025), dedicated to the memory of Lulu Peyraud of Bandol’s Domaine Tempier

In September 2010 Sommelier Journal—the precursor to The SOMM Journal—indulged my personal aspirations by allowing me to publish a 6-page interview with Kermit Lynch, my first (and perhaps only) mentor. By the late 1980s Lynch’s imports were the only French wines I would carry on my wine lists. Many of his selections were a revelation because they were practically the only wines that tasted, at least to me, real—their natural selves, not so much contrivances of commercial or even artistic (i.e., reflections of winemaking craft) machinations.

Honestly, selling these kinds of wines in the ‘80s and ‘90s was like pulling teeth. Very few consumers were interested. Whenever I sold a bottle of a Kermit Lynch import it was practically because a guest was humoring me. Mr. Lynch himself well understood that challenge. A few years ago, when I asked him to write the foreword for my book on restaurant wine management (still to be published!), he kindly obliged by writing about the first time we actually met, in March of 1990, when he somehow stumbled into my restaurant in Honolulu:

“At the table, I opened the wine list first, as usual. My wife told me I looked like a cartoon character, with my eyes bulging out of their sockets. There, on the wine list, in Hawaii, obtainable, was the Savennières from Château d’Épiré, one of my favorite dry whites, but unknown, esoteric, hard to sell. What the hell was it doing in Hawai’i?

“I roamed down the list and saw all sorts of unusual selections from France. But not just any wines; these were the dangerous ones. I asked the waiter if the wine buyer was on the premises, and that’s how I met Randy Caparoso. We became friends and he spread the word about a lot of my rather obscure wine imports. He loves making discoveries as much as I do, so we hit it off.”

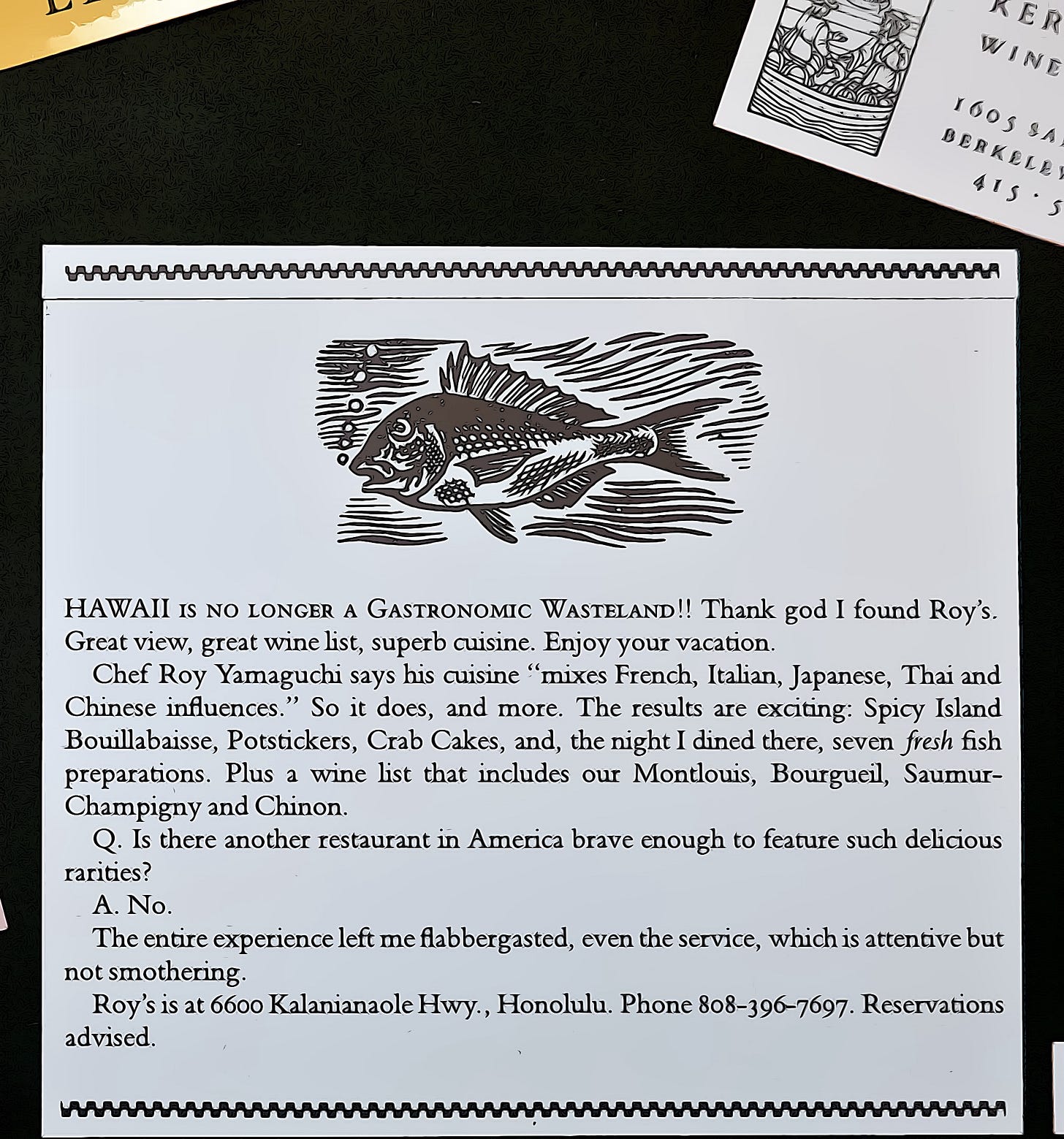

Shortly after in 1990, Kermit published this in his newsletter:

Now, of course, Kermit Lynch imports are everywhere; which is why, in 2010, I proposed a “20 years after” talk with him about favorite wines, past and present.

In 2004 Ten Speed Press compiled Kermit’s favorite newsletter passages in a book called Inspiring Thirst, which included this 1995 snippet on Bottex’s Bugey Cerdon Rosé:

“Here is one of those curiosities we import that many people are afraid to try. Fear of the unknown? Well, it is a sparkling rosé from the Savoie made from a grape variety that no one has even heard of. Plus, it is ultra-light, only 7° alcohol! Strike four.

“When I vacationed in Hawai’i, Randy Caparoso, the ideal sommelier at Roy’s Restaurant in Honolulu, invited my family to a picnic on the beach. He brought an ice chest of Bugey rosé. Of course, the sun and the waves helped, but I don’t know that I have ever enjoyed a wine more. And even in the hot sun, at only 7° alcohol, this wine does not mount to the head. Next barbecue, give your friends an utterly known, utterly fabulous treat.”

Kermit loved that beach so much, a few years later he bought a cottage just a few feet away (we last enjoyed that haven of bliss ourselves during a two-week stay in December 2023).

That said, the original text of our chats in spring of 2010…

The original paragon of terroirists, champion of unfiltered wines, and patron saint of today’s fervent followers of natural or organic wines: You needn’t subscribe to any of these religions to know that Kermit Lynch has been one of the most influential figures in the wine world since founding his revolutionary Kermit Lynch Wine Merchant in 1972; first as a retail store, and since the mid-eighties as an internationally acclaimed import company.

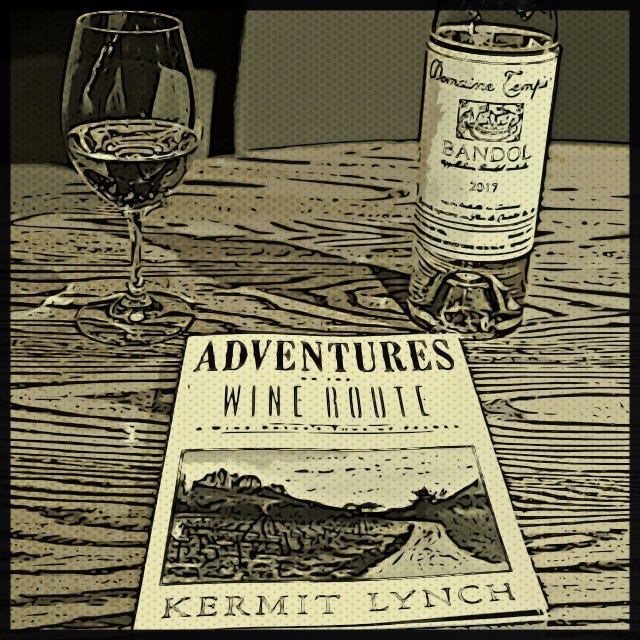

Then there’s “The Book”: Lynch’s classic Adventures on the Wine Route, published by Farrar Straus in 1988, and now in its twentieth printing (in paperback by North Point Press). One of Lynch’s biggest admirers, Winebow’s Leonardo LoCascio, has described Lynch as “the most coherent example of a wine importer… all of us spend time with our producers, but Kermit took things one step further and went to live among them.” Adventures chronicles Lynch’s earliest encounters with the most staunchly traditionalist winemakers in France, struggling to maintain the integrity of their craft beneath the onslaught of technology, modern day market demands, and the slings and arrows of outrageous critics. Lynch and his family (wife Gail Skoff, a professional photographer, and kids Marley and Anthony, now ages 21 and 19) have always split time each year between homes near Bandol (from May to October) and in Berkeley (avoiding Provence’s harsh winters).

Resulting awards have been legion: as in the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur (received in 2005), Chevalier de l’Ordre de Mérite Agricole (1998), and the James Beard Foundation’s Wine Professional of the Year (2000). In 1998 Lynch purchased the historic Domaine Les Pallières in Gigondas, which he produces with the help of the Bruniers of Vieux Télégraphe. But his proudest, recent achievements? As a musical artist, the production of two CDs—Quicksand Blues (2001) and Man’s Temptation (2009)—recorded with the backing of top-notch Nashville and West Coast musicians, and put out by Dualtone Records.

Lynch’s singing voice has been described as “a rollick with a riff-raff of raspy Rod Stewart channeling Dylan” (Ed Paladino, E&R Wine Shop, Portland). Bonny Doon’s Randall Grahm has called Lynch “the father of the reefer” (i.e. refrigerated containers). Grateful Palate’s Dan Philips says “there isn’t a day that passes when I don’t think about Kermit… he has been my mentor through example and study”—yet Philips has never even met the famous wine importer-turned-bluesman!

Last December (2009) Lynch and I met twice, over lunch at Chez Panisse and at his store in Berkeley, and began our conversation revisiting some of the producers immortalized in Adventures on the Wine Route:

Could you tell us about the changes brought by new generations among the producers you wrote about in Adventures, published over twenty years ago?

Each winery is a different story. Sometimes the transition will involve a son or daughter, working hard to improve the quality of their wines. Back when I started, it was usually the opposite. You would have a son or daughter who graduated from a school of viticulture or enology, but all they were interested in was making a stable, predictable wine to satisfy the “market,” but not the soul.

At Domaine Tempier (in Bandol), the most recent change in generations has meant nothing but good. Daniel Ravier took over with the 2000 vintage, following Jean-Marie Peyraud who had taken over from his father, Lucien. I think the wines became considerably better, almost immediately, after the winemaking was turned over to Ravier, who had to come from outside the Peyraud family.

Was this a skill factor on the part of Ravier?

There’s certainly that, but also because Ravier had already spent decades in the region, making wine and olive oil. He’s got his feet in the soil—that makes a difference. I always think it’s strange when a renowned domaine hires a renowned winemaker from outside the region, like from Bordeaux, to make their wine for them, yet it’s something you see quite a bit. Part of my definition of terroir involves the tradition of winemaking—when you start playing around with that, the wine is bound to change quite a bit. You almost end up, in this varietal world we live in right now, with wines that don’t have that character, or “thereness,” of terroir.

The taste of a grape rather than a place?

Exactly. I don’t understand fruit driven wines. Why not just buy fruit juice? I don’t get it—it’s like, “if you want fruity, this fruit juice is really pretty.”

Is the Peyraud family still involved in the operation of Domaine Tempier?

There are four sisters and two brothers, I believe, who are still the owners of the domaine; and of course, they make the big decisions—they’re the boss. Ravier is sort of the general manager who makes all the day-to-day winemaking decisions, and Lulu [Peyraud] still lives at the domaine.

What about the changes among your Loire producers?

Charles Joguet was a big transition because he had no kids.So he sold the domaine about twelve years ago, and his team stayed on.He lives there, and wine continues to be made under his name.I visit, have lunch with him from time to time, but I don’t know what his day-to-day role is. But I’ve been happy with the wines. When Joguet ran his domaine, he was not just a trailblazer—bringing Chinon up to the stature it has today—but he was also a gambler. Yet Charles tells me that the wines have been more consistent in recent years, and I have to agree.

Then unlike years past, when something “new” happens to a domaine, it is no longer something that might turn out “bad?”

You know, since I’ve started going to France, there have been big changes. There are a lot more people trying to make natural, unfiltered wine these days. When I first went over, the issue was all these squeaky clean wines with no character; with of course, the exceptions like Domaine Tempier, and Vieux Télégraphe owned by the Bruniers in Châteauneuf-du-Pape. But you also need to consider the fact that before, with a Henri Brunier, he would only bottle one out of every two or three vintages. His sons have the talent, but they’ve been able to make good wine practically every vintage. The only recent vintage they haven’t made was 2002.

So we are talking about considerably improved technology in the winery and vineyard?

Absolutely. Things are better than ever. Then there’s global warming—it’s not just talent and improved winemaking these days.

What about in Savennières, at Château d’Épiré?

There have been many changes there. Their story has always been about the same family, the Bizards, but with three different winemakers, hired from outside the family, ever since I started going there, around 1977. One of the winemakers was not very successful; and during that one period, I let them know how I felt. I don’t know how much I had to do with it, but the changes eventually turned out for the better, and the quality has been as great as it ever was during the past five or six years.

But it’s an interesting story. When the father, with whom I started working in the seventies, died in 1985, the kids immediately began to replace the old demi-muids (large oval casks) with stainless steel tanks. With the old Monsieur Bizard, I was always allowed to come in and create my own blends; but suddenly I was being offered choices strictly from stainless steel. I told them that for the Cuvée Spéciale that I imported, which always came from the oldest vines, I needed the wine to come from demi-muids rather than the sterile tanks. Eventually they came around, and now I still go back to make my blends. I prefer the traditional style of Savennières from demi-muids, but sometimes I’ll add some wine from stainless steel if it helps to make a better wine – there’s no rules when it comes to this.

I think that’s one of the mistakes that people make about me. They read my book, and they see what I think about filtration, and based upon that, they say something that I’ve never said: That Kermit Lynch imports only unfiltered wines. That’s not true at all. If I think a winemaker’s talented enough to pull it off, I prefer an unfiltered wine. But you have to start with the idea that a wine is going to be unfiltered, and take care of it in a different way. In the best of all possible worlds, all my wines would be unfiltered; but in many cases, they are not—some producers’ filtered wines may be better.

What are other examples of Kermit Lynch wines being misconstrued?

The best producers are always changing. It is a mistake to think that tradition means staying in one place. At both Tempier and Vieux Télégraphe, for years and years there would be a cuvée unfiltered made for me, and something else for the rest of the world. Neither one of them were completely behind unfiltered wine at the beginning. It was only after about a dozen years for the Peyrauds—the Bruniers took a little bit longer at Vieux Télégraphe—that they came around, and today neither one of them filters any of their reds.

Domaine Tempier has also been long associated with non-use of SO2. Have there been changes there in that respect?

Lucien Peyraud, who originally made Bandol what it is today, actually did give his wines SO2. Because of the way the wine was raised it would get reduced, and SO2 would protect it from reduction; and you could also rack it. But there would be problems with the wines, especially when Jean-Marie began making them, because he often did not rack enough. So you had wines that some people thought were refermenting in the bottle, which was actually caused by residual gas carbonique, because the wines were not racked enough.

And I presume you no longer find this in a Domaine Tempier?

Absolutely. This problem disappeared after the winemaking was taken over by Daniel Ravier, who is more of a perfectionist. It’s been the same at Domaine Joguet in recent vintages. But yeah, this thing about filtration is not something based upon some philosophical idea. It comes from tasting, and observing wines as they age. No one can talk about filtration unless they’ve had the chance to taste exactly the same cuvées, filtered and unfiltered, over a period of time. Only then do you understand what filtration takes out. People want to argue with me about filtration, but I don’t want to argue with them unless they’ve tasted wines over the years and made the comparisons. Then you find that in almost all instances, the filtered wines lose their color and their aroma, and the unfiltered wines don’t—99% of the time. Unfiltered wines, both white and red, retain so much more flesh, so much more flavor.

Talk about your years working in Burgundy to find the wines you like.

Most of my reds from Burgundy are unfiltered, and most of the winemakers I know have been excited about it. This idea of filtering originally came from somebody telling the winemakers that the market won’t accept wines that are bottled with some little speck of something or another. But these days when I tell winemakers that I want my wine unfiltered, they say, “yeah, great… I wish everybody were like you!”

But in the past, the story was different: Owners who would say, “it’s just had light filtration.” Then I would have to ask, “what do you mean by ‘light’?” And they’ll talk about using cardboard, or diatomaceous earth. There was one of them, who started off by telling me he only does “light” filtrations, and explained how he filtered a wine with a cardboard box #3, which is a pretty wide filtration that takes out the flies and everything; and then how he filtered it with a #7, which takes out just about everything. After that, he did a sterile filtration. I asked him why, and he said, “well, my wine is so dense that it won’t go through the sterile filter if I don’t do the other filtrations.” What’s amazing is that you’re tasting his new vintage, which is black, and so delicious, coming right out of the cuve. Then he pours his wine from last year, which has already been bottled, and filtered like hell, and it tastes more like rosé!

Can you talk about your experience in Beaujolais; which, it seems, has become more popular after a long period of relative disinterest?

For my producers, that’s been very true—we’re selling more great Beaujolais than ever before. Restaurants are eating them up; probably because people are catching on to how versatile wines made from Gamay are with food—certainly a refreshing antidote to many of the over-priced reds you see these days. But overall, the Beaujolais region is suffering.

In what ways?

It is the quality producers—like Foillard, Lapierre, Thévenet and Breton—who are doing great. Others in the region are seeing the trucks coming by, picking up all the wines the good producers can make. There’s going to be a pendulum shift towards wines that are the opposite of what you see mostly in Beaujolais; from vineyards in which there has been no real cultivation other than for huge production of weak wines, with heavy use of herbicides and pesticides. In these vineyards there is nothing growing between the vines, just bare earth, no life. That’s going to change, and the pioneers like Lapierre, and the “Gang of Four,” have been leading those changes. They’re succeeding because they get a lot more money for their wines, of course, and in recent years there have been more like them.

So economics will play a big part of the changes in Beaujolais?

I saw a Morgon recently in New York–I believe it was a Duboeuf–that was on a shelf for $12 a bottle. Lapierre is up around $26, $27, and we can hardly keep it on the shelf. Other winegrowers in Beaujolais are seeing this, and they’re saying, “I’m going to change.” Just like Côte-Rôtie was transformed by Guigal; although in that case, not exactly for the better. Côte-Rôtie used to be a gem of a Syrah, with natural, exotic aromas, and now it’s not—it’s become more about tannin and oak.

Speaking of which, where is Kermit Lynch currently at in the Northern Rhône?

I’ve got a very interesting new Côte-Rôtie coming out under my own label this coming year; something I put together, showing what I think Côte-Rôtie is about. Of course, the two that I already bring in, from Philippe Faury and Jasmin, I like very much—they’ve always been known for finesse, and I’ve been working with them for a long time. Especially Faury, because he has always let me do my own blends, and it’s not done in an oaky style.

So if a producer, from Côte-Rôtie or elsewhere, decides to change to a less finesseful, oakier style, would it be safe to say that he may no longer find a place in the Kermit Lynch portfolio?

He wouldn’t, but he’d find another importer real quick! Then again, most people think Côte-Rôtie is a heavy, oaky, alcoholic wine. That’s not what it always was, if you read the literature from the past.

What about for Cornas?

Circumstances in Cornas, for some reason, are a little different. If you look at the Northern Rhône, Thierry Allemand and Clape stand out as two great, great winemakers, and it’s almost by chance that they’re both in Cornas, and both at the top of their game. No matter which appellation of the Northern Rhône they would have been in, they’d probably make the best wines.

Then again, wouldn’t many people say Guigal is the one on top in the Northern Rhône?

Well, yes, obviously I’m losing that battle, too (laughter). Guigal sells for hundreds of dollars, and my two wines from Cornas are more like $50 or $60.

Let’s go back to your Gang of Four from Beaujolais, and the issues that have always been raised concerning unsulfured wines—something that in a lot of ways is identified with Kermit Lynch imports…

It may come as a surprise to many people to know that I don’t believe that unsulfured wines are necessarily the purest. I’ve been working with all my producers on this, in all the regions. In Beaujolais, yeah, we have seen too many wines gone wrong, but I haven’t had a problem with instability since I began talking to my producers about this, going back at least the past two vintages. And they all agreed—they all knew there were problems in the bottle, and so they are now using the small amounts of sulfur we are asking them to. Minimal doses, but at least 15 grams.

We are requiring this from all of them, that is, except Lapierre. I want to continue working with unsulfured wines with Lapierre because we taste together so often, sharing ideas like: If you want to bottle without sulfur, do you bottle early or do you bottle late; do you do it in stainless or do you do it in wood; in barrel or in foudre? With Lapierre, I want to see how stable a wine we can make without sulfur, and I think he would be the best one to work with.

The first significant Beaujolais that I imported, back in 1979, was by Jules Chauvet, the original instigator behind the Gang of Four. Chauvet was also a microbiologist, and I never had stability problems with his wines. I only imported three vintages before he died, but those wines were so… “my god.” The aromas were what I call “cornucopian”—so much in there to entice you. Yet Chauvet had no grand crus, just Beaujolais Villages—he was that good.

My thinking about unsulfured wines that prove unstable in the bottle is that it’s not fair to the customer, and it’s not fair to the wine. How many great wines have I seen that were bottled without sulfur, but somewhere along the line—a month or six months, or two years later—became undrinkable? What is the virtue of that? I do feel a little responsible for being part of this almost religious fervor for non-SO2 wines. Based upon good experience, from 1979 until about two years ago—you’re talking about almost thirty years of experimentation—I’ve since made the decision: If it’s done well, sulfur is a great gift.

Recently an MS/friend told me about how he much enjoyed a five year old bottling of your Beaujolais AOC, which was formerly bottled under the Kermit Lynch label, and now as Domaine Depeuble. He found it to be perfectly fresh, in immaculate shape. What’s up with that?

Here again, the Depeuble is bottled unfiltered, so I’m not surprised to hear that. One year we found a case of Depeuble’s Beaujolais Nouveau that had been buried in the warehouse for almost two years—long past the usual expiration date. We pulled a bottle and opened it, and here it was: Being unfiltered and unsulfured, it had a deposit more than an inch deep—just thick—and it was unbelievably fresh. That deposit, I think, may have had something to do with it, nourishing the wine and keeping it alive. I love everything about Beaujolais Nouveau, and that’s why we celebrate it each year. But most of them are pasteurized, cold stabilized, sterile filtered, and sulfured, yet they’re supposed to be drunk right then and there. It’s unbelievable—there’s no reason to do this to a wine you drink immediately. You taste Depeuble’s Nouveau, and what do you get? Ba-bammm! Being unfiltered and unsulfured makes all the difference in the world.

In Adventures, some of your most quoted passages have been about wines that are made to attain high scores, as opposed to going with food. How have things changed in that regard?

Unfortunately, today wine is made to score points, even though wine was originally made to go with food, or just to make you feel good. Another thing about scoring wines that is so false is that you end up with winemakers in places like Muscadet, putting their wines in new oak to make it taste more like Montrachet, because they think they’re going to get higher points. I don’t get that, because first of all, you can’t ask Muscadet to be Montrachet. It stands to reason that the most perfect Muscadet in the world deserves a score of 99 or 100 as much as a Montrachet. The “good” Muscadets you see around are tagged with scores like 88 or 89. Regardless of the score, a perfect Muscadet has its function, and it’s never going to be the same as a Montrachet’s. But scores today are even more important than when I first wrote my book—so that’s another battle that I’ve clearly lost!

But you have to understand, or readers should understand, that most people in this country think that, “I can’t trust my wine merchant.” Or, “I can never trust Kermit Lynch because he’s trying to sell me his wine.” They never stop to think that it is the critic who is trying to sell his journal or his magazine. It’s a little twisted, but that’s the mess scores make of everything. They all do it—everyone is peddling their scores, so many of them that the message has become hopelessly diluted—and now we’ve even got critics and magazines in France doing the same.

Well, presuming sommeliers are not as gullible as consumers: What career advice would you give to our readers, the sommeliers?

It’s one of the bright spots in the wine world that I see so many sommeliers, and so many wine lists, that aren’t paying attention to scores. They’re not paying attention to fame; they’re trying to buy wines that they think are interesting. Early in my career I got the reputation of bringing in esoteric wines, but when I go to some restaurants now, I have to ask, “what’s this, where’s this from?” Sommeliers these days are much more daring, and it’s fabulous.

But for advice, here’s something a little more specific: I’ve been traveling quite a bit lately—something I haven’t done in a long time—to places like Boston and Portland; and of course, I’ve been traveling mostly to promote my CD (Man’s Temptation, released in early 2009), and pouring a little wine on the side. In restaurants, like at home, for white wine I’ve always liked a good white Burgundy. So what I noticed, in New York and a little bit in the Bay Area as well, is that when you go to a wine list and locate the Burgundy section, and you look for a Chablis AOC, you cannot believe the crap—I’m sorry, I can’t find a better word—that you end up finding. It’s all négociant wines! You go to look at sections for other regions, and you see these really good wines from great growers. I don’t get it, because there are so many great growers’ wines made at the AOC level, from Chablis as well as Mâcon and Vézelay; and they’re so cheap, why settle for something from a négociant?

Somebody told me that if a restaurant wants a special cuvée from an importer, then you make a deal—you can get the wine if you sell a few cases of this other wine, by the glass or whatever. Okay, but what I do understand is that sommeliers today also have the chance to do something special: Before, you know how Americans were, they used to say, “I won’t drink a Meursault, I have to have a grand cru Meursault”—and that was the American way. Now people are hesitating at the price of crus Meursault, and so here’s the chance for sommeliers to turn people on to all the exciting Meursault—or AOC Chablis, Mâcon, and don’t forget Rully—that are out there. That’s an area a smart sommelier can concentrate on, and make a lot of people happy.

Today, of course, there is also a lot of consumer interest in Biodynamics, and you have a few of them.

We have several, but I have to think about who exactly they are I know the store staff can rattle them off, but it’s not something I keep at the forefront of my mind because, you know, I never select wines based upon that.

Well, Ostertag is a certified Biodynamic producer that restaurants and retailers know well…

Ah, yes… and so is Kuentz-Bas… Lapierre… then there’s Breton in the Loire… the Cairanne that I import (by Domaine Catherine le Gœuil)… and several more who are organic. It may not be a coincidence that producers I like happen to be organic. But it’s funny, it’s never something I ask when I speak to producers–whether they are organic or Biodynamic.

Of course, I can talk about Les Pallières, which I own with the Bruniers. We grow organic, and we have the soil to prove to people that we do. But to get the certificate you have to endure another layer of bureaucrats coming through your cellar, and then you have to pay for that privilege. Like many others, we don’t want somebody to tell us how to make the wine, or what we should do in the vineyard—and to pay the money, not knowing who exactly is getting that money? I don’t know what the deal is, but I know many of my growers certainly could never pay for certifications, which can run you in the thousands.

Earlier you mentioned starting off with a reputation for being esoteric. What’s “esoteric” for Kermit Lynch Wine Merchant these days?

I’m bringing in a lot of Vermentino, sometimes blended but sometimes pure, from Liguria. Our Punta Crena Vermentino just blows you away. Also from Liguria, there is a new Pigato (by Fèipu dei Massaretti). The Pigato grape makes a beautiful white wine, similar to Vermentino; but contrary to what’s been told, it is the not the same grape as Vermentino. That’s been something of a favorite project for me. These wines are sort of like Pinot Noir in the way that they’re so impressionable, or transparent. What’s growing around the vineyard kind of affects the way it smells—the minerality, or the salt from the sea, come right through it. This is the stuff that turns me on.

The quality of garrigue?

Yes, what they call maquis in Corsica—the spicy, herbal quality of the surounding scrubland. This is especially true of the Vermentino whites we bring in from Corsica. I’ve just brought in a new producer from Cap Corse, at the northern tip of Corsica, where it juts out into the Mediterranean. As you know, Cap Corse is where I started in Corsica in 1981, with the producer Clos Nicrosi; but there was a change of ownership there, and I had to quit working with them. Just recently we had a staff tasting of our new ’07 Raveneaus from Chablis; and lined up beside all of them, we had this rosé and Vermentino Cap Corse from our new guy Domaine de Gioielli. Our staff knows full well the style of Vermentino from Patrimonio by Yves Leccia and Antonio Arena, which grows in limestone, and tends to be very full bodied, very fleshy wines. Cap Corse Vermentino comes from higher altitudes, and from different, schist type soils, and we couldn’t help but notice, “my god, this is like Chablis is to Meursault,” when comparing Cap Corse to Patrimonio, even though the two appellations are adjacent to each other.

Gioielli is a neighbor to Clos Nicrosi. I’m not sure if the wines will prove to have the same magic we’ve always found in Luigi’s Clos Nicrosi, but we’re excited. Sometimes I think when I retire I’ll write a book called The Ones That Got Away, because there’s so much in the stories about what came between us and the producers we used to work with, like Clos Nicrosi, and Domaine de Coujon, where we did three vintages of that beautiful, Rolle based white wine from the Languedoc’s Coteaux de Murviel.

Or like that Tursan by Baron de Bachen that I used to be so much in love with?

Yeah, like Tursan… like the girl who got away… oh, the stories we could tell…

Then again, there are the Bruniers at Vieux Télégraphe, and Clos Ste. Magdeleine in Cassis, also celebrated in your book—producers you’ve stuck with from the beginning…

For Magdeleine, it’s been since 1976. Why? Their Cassis blanc just keeps getting better and better! I still work with François Sack, although just this year his two sons have started assisting him—two kids so beautiful, I’m surprised they aren’t movie stars.

Well, let’s hope the Bruniers and the Sacks never make it into that book on The Ones That Got Away.

No, I suspect they never will!