These are the good old days. ⏤Carly Simon

An exercise in bio-writing unrelated to any prospective publications, serving as an interesting peek into the modern day evolution of the wine industry.

2025 marks my 15th year living in Lodi wine country. Although I am originally from the Hawaiian Islands, Lodi has become my adopted home; and in many ways, this residency represents a culmination of a career as a full-time wine professional spanning four and a half decades.

Even I wonder where the time goes. When I first landed a position as a working sommelier back in 1978⏤transitioning from bussing and waiting on tables while working through college⏤I truly did so with a simple thought: “What a cool job⏤tasting wines and writing wine lists, opening bottles, talking wine all night with thirsty customers... and getting paid for it!”

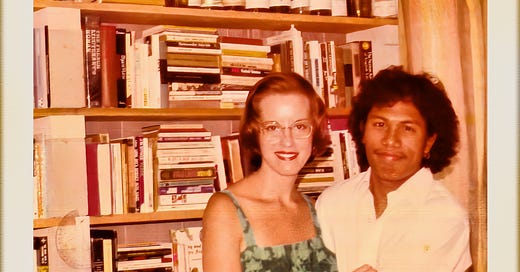

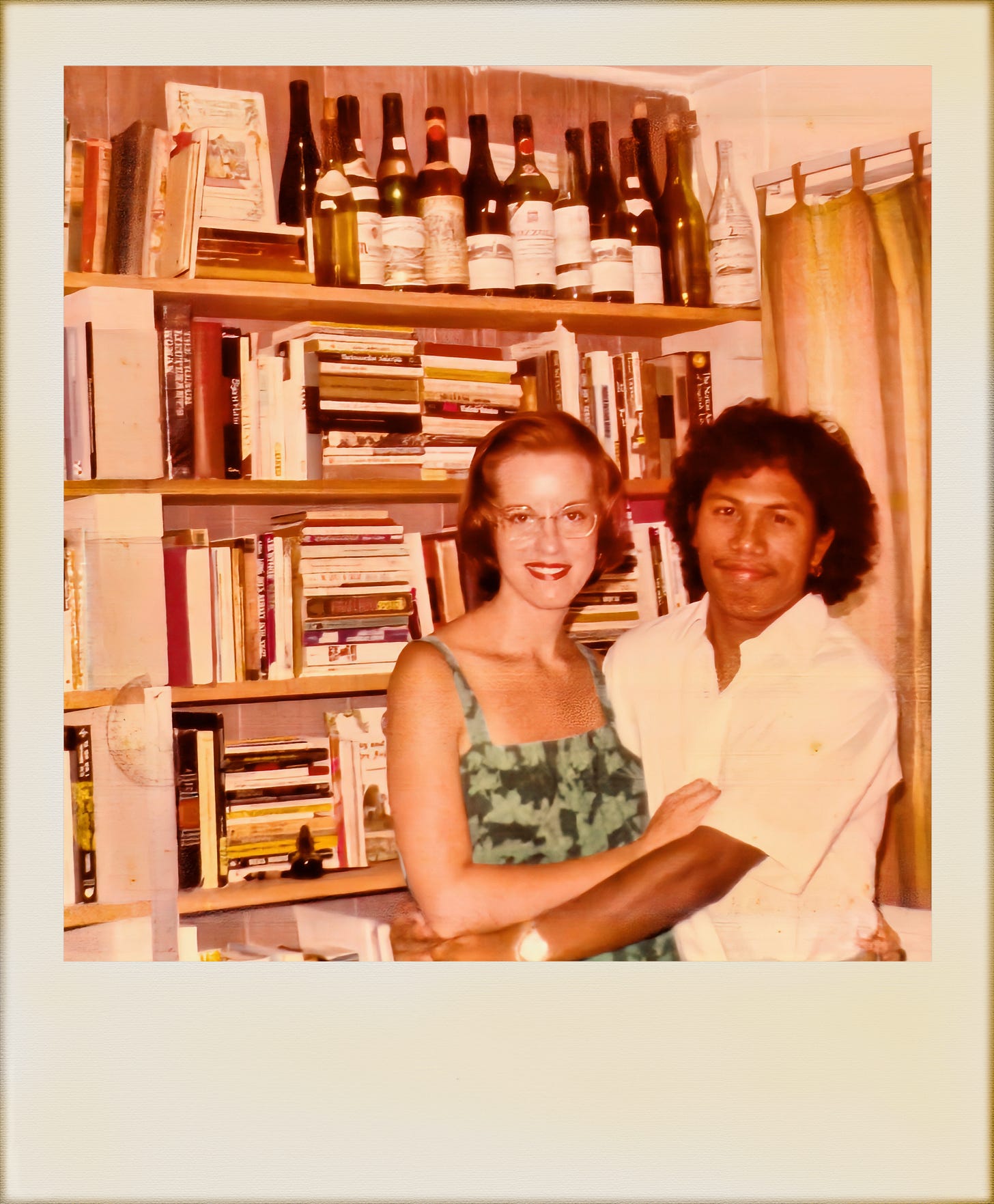

I was, and felt like, a 21-year-old just beginning to feel his oats, but I also took the job seriously because I had just gotten married to a fellow University of Hawaii student (who loved cooking, just as long as I brought the bottles!). In 1978 we were expecting the first of (eventually) four fantastic children. I needed a real paying job⏤preferably doing what I loved best⏤especially since I had spent the previous four years pursuing a less than useful subject (philosophy).

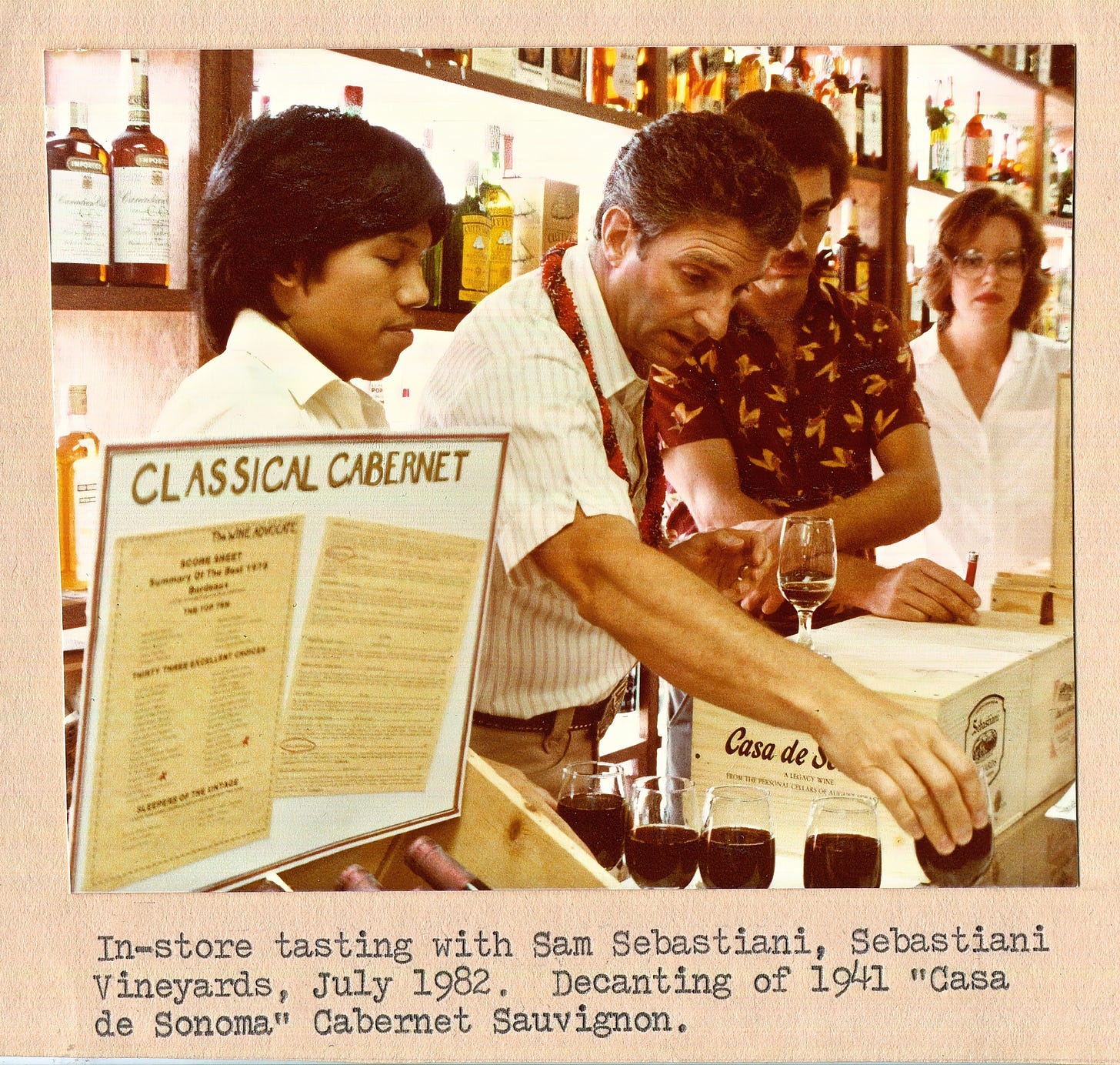

Yet wine, to me, was more than a living. It was an obsession. From the moment I first caught the bug, after attending a restaurant staff tasting at the age of 18, I began planning trips to wineries and vineyards in California, then the Northwest, and later Europe. In the late ‘70s and early ‘80s the wine industry around the world was just a fraction of the size of what it is now, and not nearly as many Americans even touched the stuff.

Therefore, in those days, even the greatest wines were not in huge demand. We could buy the Château Lafites and Moutons, Pétrus and d’Yquems, and all the grand crus of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti for under $40 or $50⏤tasting, evaluating, and consuming these wines to our hearts’ content. I remember buying all-time classics like ’68 and ’70 Beaulieu Private Reserve for $12 each, and ’70 and ’74 Heitz Martha’s Vineyard for (gasp) $25 or $30.

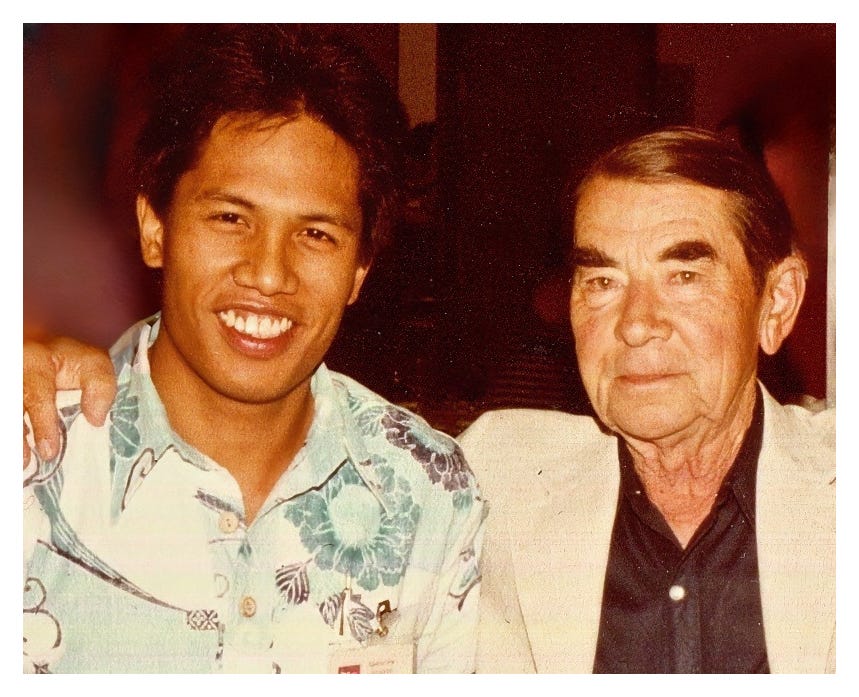

Being part of the burgeoning industry in the 1970s and ‘80s also meant being privileged to personally meet and befriend many of the California pioneers⏤André Tchelistcheff, Robert Mondavi, Justin Meyer, Paul Draper, Myron Nightingale, Dick Arrowood, and so many more⏤on a first-name basis. People like Schramsberg’s Jack and Jamie Davies, Kermit Lynch or Jess Jackson himself would sit down at a table with you; and at least once a year I would fly over and call on them. One of my fondest moments was meeting Domaine Tempier’s Lucien Peyraud and his wife, the famous Lulu, in Provence, a longtime place of dreams.

These, of course, were the days before email, or even fax machines. Phone conversations were rare⏤I’d write letters, and they’d write back. But when you did meet, you could ask questions, and they would take all the time needed to help you understand what they do, and how they do it. You could talk to the old industry giants, when they walked the earth.

Nowadays, mind you, young sommeliers have even more opportunities, and certainly far, far more wines to choose from. Today’s sommeliers, frankly, are also required to be significantly more knowledgeable than we were, 30 or 40 years ago. The difference, once you accumulate over three or four decades of experience, is that you gain perspectives you could never conceive of as a young professional, and you learn why there is such a thing as déjà vu.

In fact, a lot of people forget that being a young wine professional in Hawaii during the 1970s and '80s was, and still is, a big deal in itself. The first two American Master Sommeliers, for instance, lived and worked in Hawaii. The first combination Master Sommelier/Master of Wine also lived in the Islands when I started my career. This is the caliber of wine professionals with whom I worked, socialized, and occasionally tasted with⏤although honestly, I mostly kept my distance, conscious of carving out my own identity (I took Dylan’s caveat, don’t follow leaders, seriously).

Nonetheless, when the U.K.’s Court of Master Sommeliers decided, in 1988, to hold their first examinations on American soil, I applied to be among the 20 American sommeliers to undertake that challenge. Only one of us passed on that occasion, but a good number of that first group went back to eventually achieve an MS title. In 1992 the Institute of Masters of Wine also held their first, invitation-only examinations on American soil⏤which I actually passed, although it was just to qualify for final exams held (in those days) only in London.

I never got the opportunity to actually sit for MS or MW finals. Why? I was preoccupied as a husband and father⏤attending games, playing in the park, enjoying the family meals, the things parents are supposed to do with their kids⏤while working 60, 70 hours a week in retail stores by day and walking restaurant floors at night. At the same time, bolstering my ability to do my job (and, frankly, to up my value and pay) by plotting never-ending swings through the vineyards, my personal Holy Grail.

Do I ever regret not taking the time to attain the ultimate “Master” credentials? Not one second. Today, my kids are all amazing adults accumulating their own life-experiences, no doubt better than mine, and I am now a grandfather of six. Those are the rewards.

In 1988 I was still working as a full-time sommelier when I met a nationally acclaimed, James Beard Award winning chef named Roy Yamaguchi, who had moved to the Islands to escape the craziness of West Hollywood. Chef Yamaguchi said he planned to open a “few” restaurants, and invited me onboard as a founding partner, manager and wine director for what promised to be another crazy ride. It was.

By 2001 I had helped open no less than 28 of these “Roy’s” restaurants, specializing in cutting-edge French-Asian cuisine and equally innovative wines, which I traveled to globe to find. In doing so, I got the opportunity to spend tons of time in markets from coast to coast⏤in multiple cities in California and Florida, from Washington to Georgia, Chicago to Austin, Denver and Scottsdale, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and more⏤while working out of home offices in Honolulu and Newport Beach, California.

Because Roy’s was such a high profile group⏤and working for a groundbreaking chef, a built-in advantage⏤I earned accolades of my own; highlighted by awards such as Santé Magazine’s first "Wine & Spirits Professional of the Year" (1998), and Restaurant Wine’s "Wine Marketer of the Year" (1992 and 1989). At one point, in the early ‘90s, our original Roy’s Restaurant in Eastern Honolulu was rated among the country’s Top 40 (by Gault Millau and Forbes). No matter how you slice it, this was a pretty big deal.

Make no mistake, our restaurant success grew out of plain ol’ elbow grease (the quality of our work was our hype) with a good measure of raw ambition. Sometimes I would pack a bag and not get back home for over a month (so much for being decent family man); especially when there were West or East Coast wine festivals to attend, and the need to personally attend to bottlings (at least a dozen at a time) grown and custom-produced for our cuisine by some of the best and brightest winemakers in California, Oregon, Central Italy, Southern France, Germany’s Pfalz and Baden regions, and even South Australia. Naturally, I qualified as a United 100K member. I could pack a carry-on with the best of ‘em.

Eventually our cozy, little “family” of Roy’s restaurants grew to be a cold, calculating, machine-like corporation. My enthusiastic, and admittedly uncompromising, approach to wine programming was not appreciated by all our new incoming executives. Something had to give. 9/11 (our New York restaurant, where I had been just two days earlier, was located just one block south of Ground Zero) left a bad taste in everyone's mouth. I parted ways with the company I helped found, and shape, shortly thereafter.

In the early 2000s I found ways of working for myself that could keep me moving from coast to coast (having developed a taste for that)⏤first as the proprietor of my own Caparoso Wines label (terrific wines, and an even better way to lose money!), and then as a restaurant consultant (spending extended time in cities like Denver, Memphis, St. Simons Island in Georgia, and Winter Park, Florida).

In 2008, while hunkering down in Colorado’s Front Range, I met an entrepreneur who had successfully published medical journals. He had it in mind to start the first-ever professional journal (at least in the U.S.) written and published exclusively for the sommelier trade. It just so happened that, while working in restaurants, I had also accumulated over 20 years’ experience in the discipline of writing biweekly newspaper wine columns (starting in 1981 for my hometown newspaper, The Honolulu Advertiser), while publishing numerous freelance articles for restaurant and wine industry publications.

This Colorado connection led to the founding of Sommelier Journal (in 2007); which eventually morphed into The SOMM Journal, for which I am currently the "Bottom Line" columnist and West Coast Editor-at-Large, while also leading sommeliers on frequent 3-day, on-site studies from British Columbia all the way down to Santa Barbara. I think of these sommelier “Camps” as a way of making it possible for today’s on-premise professionals to learn the trade in the same ways I was fortunate to experience in my 20s and 30s⏤by getting out into the field and walking vineyards, not just through books and tasting wines within the four walls of restaurants.

The funny thing (at least to me) is that for years I told people that I worked as a restaurant wine professional, and wrote wine columns on the side just for fun. Today I earn my keep by writing wine columns (and blogs, particularly for lodiwine.com), and I occasionally do a little restaurant consulting on the side, mostly for fun..

When I started in the business, wine lovers and wine producers from all around the world used to come to us, in the Hawaiian Islands, and that’s how we learned what people loved, and how wine producers thought. Later in my career I was given the means to get out into the world; meeting wine lovers in their own hometowns across the country, while increasing my time up close and personal among vines, tasting wines from barrels and bottles while picking the brains of our greatest vintners.

But here’s another funny (or not) thing: No matter where you go⏤and I’ve been to enough places⏤you find that all consumers crave real, genuine wines, at their finest (no matter what the price point) when they are expressive of the places they are grown; while growers and producers of the world’s finest wines are cognizant of pretty much the same things, even when their work is more commercialized than artisanal. It’s like the old Paul Simon song about “The Myth of Fingerprints,” I’ve seen them all and man they’re all the same. That is to say, the reasons why wine is universally loved.

In any case, I am now a senior citizen, leading a contented life ever since Lodi grape growers invited me to pitch a tent in their backyard in 2010. I am no longer obsessed with going everywhere, seeing and tasting everything; not even in places I have yet to set foot (like Austria or Argentina, New Zealand or South Africa). I know a lot of this is something of a late Boomer’s rocking-chair laziness, but hideously long plane rides no longer enchant me, although I will drive two days just to watch my grandson play piano, or hear my youngest granddaughter laugh.

I am no Liam Neeson, but I am grateful that, in Lodi, I found a community willing to let me share my particular set of skills, and make a difference. It is precisely because of my previous experiences that I know Lodi⏤its vineyards and terroirs, wines and people⏤is the real deal, and I find the fact that most wine lovers in the world don't know about it actually appealing. I’ve always thought, it’s wine professionals who are up to challenges who do the most interesting work. Something to actually write home about.

It is also precisely because of my experiences that I know that wine consumers in general are no idiots. They always thirst for “more,” and have as much capacity to appreciate wines as professionals in the industry and trade. If they didn’t, most of them would still be drinking wine coolers, Lancer’s Vin Rosé or "Riunite-on-ice." The stupidest thing anyone can ever do is underestimate consumers, many of whom are perpetually ahead of presumed experts in the media or trade. Consumers know.

All I know is that from the centralized location of my wine country home, I can now do what I have always loved the most: Revel in the endlessly fascinating beauty of vineyards, the conviction and resourcefulness of growers, the artistry and science of winemakers, and above all, the sheer joy and warmth of everyone associated with the life of grapes and good, honest, decently made wine.

If this be the life of wine, lock me up!

Please feel free to write Randy Caparoso at randy@caparoso.com and find access to all his published articles since the 1990s at authory.com/RandyCaparoso.

Beautifully done!

Great story of a life well lived. One thing you left out, which I feel obliged to mention, Randy, is your mastery of vineyard photography. Some of the best anywhere.